![]()

Copyright 2001 Ha'aretz

September 6, 2001

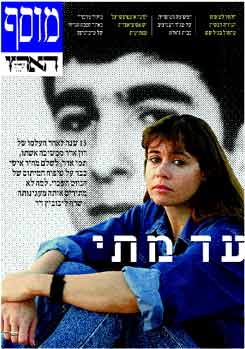

Who Will Save Tami Arad?

Fifteen years after the disappearance of navigator Ron Arad, his wife Tami still remains an aguna,`chained' to her marriage until he is declared dead.

Why is no one in the defense establishment prepared to do so?

By Sara Leibovich-Dar

In mid-October, it will be 15

years since Israel Air Force navigator Ron Arad was taken captive.

To mark the occasion, the Ron Arad Foundation (Ha'amuta Lema'an Ron

Arad) is planning to stage a demonstration by thousands of Jewish

youths in front of the United Nations headquarters in New York.

United States senators and congresspeople will also take part. New

York Senator Hillary Clinton has been invited. Foreign Minister

Shimon Peres, who was prime minister when Arad was captured, has

promised to attend. In Israel, a million blue balloons, chosen to

symbolize the campaign on behalf of Arad, will be released into the

air. Schools will focus attention on the missing and captive Israeli

soldiers.

"We're working to keep the Arad issue on the

agenda," says Tzur Heres, a childhood friend of Ron's who is active

in the foundation. But there are also those who think that 15 years

after Arad went missing, the time has come to concentrate efforts in

a different direction altogether - on lifting the years-long aginut

(from aguna, literally, "chained woman") of Tami Arad. (According to

Jewish law, a woman with a missing husband whose fate is unknown is

not free to remarry. She is "chained" to her marriage until proof of

the husband's death can be established).

"She should be

freed from her aginut," says Tami's father, Nissan Gilad. "It's

totally clear why this should be done, but the problem here is very,

very complicated. We know it's a complicated thing. The Defense

Ministry is handling it."

Rabin's dilemma

About six months before Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated, she

asked him to look into the possibility of removing her aguna status.

For that to be done, Rabin would have had to declare Ron Arad a

casualty of war whose burial place is unknown. Eitan Haber, the

former director of Rabin's office, recalls that the topic came up

once in a conversation between Rabin and Arad. Rabin turned to the

military rabbinate.

"This is a story that belongs entirely,

for good and for bad and from top to bottom, to the rabbis. I can't

imagine a secular body imposing something on the rabbis in this

area," says Haber. "Rabin agonized over it a lot," says Heres. "It's

our dilemma as well. We, Ron's childhood friends, talk about it

quite a bit. What would we tell him if he were to show up one day?

What did we do for him all these years?"

Avihu Ben-Nun,

meanwhile, believes that the process ought rightly to begin at the

military level. "They're the ones who should bring the rabbis the

facts, on the basis of which they'd be able to free her from her

aginut," he says. But the military appear to be in no great rush.

Deputy Defense Minister Dalia Rabin-Pelossof says that, as a

woman, she understands Tami Arad's distress. "In principle, leaving

a woman as an aguna is a cruel, terrible and wrong situation; but

the whole problem is very delicate and complicated. Also, this is a

case of a military man who fell into captivity, and we have no

evidence that he is dead. On the contrary, [indications] point more

in the direction that he is alive. And there is also an obligation

toward Ron Arad's mother. My father met with Tami Arad, but he was

also sensitive to Batya Arad."

Alone on the

battlefield

The lesson to be drawn from the Arad affair

is that smart women should never be wed in a religious marriage,

insists former Knesset Member Shulamit Aloni. "In the enlightened

world, when a man disappears, the court can annul the marriage after

five or seven years. Our rabbis are stricter because they hate the

secular in general and women in particular.

"Tami Arad is a

victim not just of the religious, but of the army, propaganda and

myths. The army is playing a hypocritical game with her," Aloni

continues. "No one is bold enough to say that he is dead because the

Ron Arad cult is convenient for the army. In his name, they

kidnapped Sheikh Abdel Karim Obeid [in July 1989] and Mustafa Dirani

[in May 1994], bombed Lebanon and accused the Iranians of kidnapping

him. The army has done public relations for itself, twisted though

they may be, on the back of Ron Arad. And everyone - all the lawyers

who have dealt with the issue over the years - knows the truth, but

cooperates with the army because, otherwise, the army won't work

with them anymore. And you can't berate them for it, because how can

you demand that people be courageous? Arad has been an aguna for so

many years because she lives in a society in which a woman's life

and fate are not regarded as important."

"I have no idea

what's happening as far as [the aginut matter] goes," says attorney

Amnon Zichroni, who was involved in international contacts aimed at

finding Ron Arad. "I didn't deal with the family issues. I conducted

negotiations with various officials around the world, but I wasn't

in contact with the families. I suggest you talk with Ori Slonim. He

is in contact with the family."

Attorney Slonim says his

involvement in the case never had anything to do with relieving Tami

Arad of her aguna status. "I dealt with the effort to locate him,

though the subject of her being an aguna was constantly hovering

over all of us. But it wasn't my job to deal with that."

When asked why he didn't try to see that Tami Arad be freed

from her aginut, one former air force commander says: "In our

assessment, he is in captivity. The moment we remove her aguna

status, we're admitting that he's not alive. This means that, on the

one hand, the State of Israel would be officially declaring that he

is not alive while she continues to demand his return. It doesn't

make sense. How can you seek him on the one hand and simultaneously

release her from aginut? Of course, she wants to live her life. It's

very cruel."

Rabbi David Levin, who formerly oversaw the air

force branch dealing with injured servicemen and is currently the

director of the Defense Ministry's rehabilitation department in

Haifa, says that becoming an aguna is one of the most difficult

things that can happen to a woman.

"It pains me, as it pains

every other Jew. It is so terribly, terribly hard. She's stuck in a

situation that's neither here nor there. She is caught, trapped. And

she can't do anything about it. Being a widow would be preferable."

Why haven't you tried to help her?

"There's no clear

basis on which to release her from this status. It's impossible to

say whether Arad is dead or alive. There was clear evidence that he

was alive. There are letters from him, then he disappeared and no

one is saying that he is dead."

The Ron Arad Foundation is

not putting its resources into helping Tami Arad with the aginut

issue. Yosef Harari, the foundation chairman, says, "We stay away

from that. It's her business. Like the Israeli government, we in the

foundation argue that he is alive, thus there's no basis for talking

about lifting her aguna status."

And so Tami Arad is left to

cope with the aginut problem almost completely on her own. In a

private meeting with air force pilots several years after Ron's

disappearance, she expressed the hope that all the men sitting

before her would, "before going out on a mission, come to an

agreement in writing with their wives as to what should happen if

they ever fall into captivity."

In their book, "Hata'aluma"

("The Mystery," Yedioth Ahronoth Press), Ron Edelist and Ilan Kfir

write that Tami Arad also appealed to Shimon Peres in the matter:

"He didn't hide from her that the subject was very sensitive and

problematic. She asked to be treated like the widows of the men of

the Dakar submarine, who were released from aginut. Peres promised

to personally handle the request right after the 1996 elections. But

then Peres was defeated and the new prime minister, Benjamin

Netanyahu, did not deal with her request." In fact, at an October

1996 meeting of the Knesset Defense and Foreign Affairs Committee,

Netanyahu asserted that he was convinced that "Ron is alive and

we'll be able to bring him home."

After Edelist and Kfir's

book came out a year ago, Arad quickly issued a clarification in a

press release: "I did not ask for Ron to be declared an IDF

casualty. There is no reliable information indicating that Ron is

not among the living. Most of the reports and assessments from all

the authoritative sources that have been passed on to the family

since Ron was taken captive indicate that Ron is still alive."

Agunot for a year

The IDF spokesman does not

have any precise statistics on the number of women who were

eventually released from aguna status after their husbands

disappeared in the course of a military action. A former air force

commander estimates that there are between 10 and 15 such women

whose husbands served in that branch of the IDF. Most were released

from aguna status within a year of the day on which their husbands

vanished. Most did not request to be released, as they were still in

the throes of grief. The air force made all the necessary

arrangements and asked the women to consent to a declaration stating

that the husband was a military casualty whose burial place was

unknown.

Most were released from their aginut in a process

so swift that a few, still struggling to come to grips with the loss

of their husbands, refused to cooperate with the air force. Looking

back, however, some say that as painful and patronizing as the quick

procedure was, it did in fact help them rebuild their lives. Not one

can understand why Tami Arad has been left an aguna for 15 years.

Other women have fought to win their freedom from aginut. "I

led the way," says Yael Arzi. Her husband, pilot Yitzhak (Aki) Arzi,

disappeared on December 1, 1967. His plane, which had been on a

photographic mission in Egypt, was hit by Egyptian fire and exploded

in the air above the Suez Canal. The crew of a Greek ship sailing

nearby saw Arzi and his navigator, Elhanan Raz, parachute into the

sea. Arzi's helmet was found near the ship. At first, the army

believed that the two had been seized by the ship's crew and

transferred to Egypt. The Egyptians denied it. Upon their return a

few months after the Six-Day War, the Israelis who had been captured

during the fighting also affirmed that they had never been joined by

two new prisoners.

The search for Arzi and Raz went on for

10 days. Their bodies were never found. "A few weeks after he

disappeared, I realized what it meant to be an aguna," says Yael

Arzi. She was then a young woman, the mother of two daughters. Since

then, she has remarried, had another daughter and later divorced. "I

understood that my human rights were being taken away from me, that

I couldn't do anything for myself, that I was dependent on the army

for almost everything.

"The laws at the time were dreadful.

A woman could only get a passport if her husband signed the form. I

couldn't get a passport. I had to get the army to sign for me. If I

wanted to take a bank loan, I needed the Defense Ministry to sign

the forms. I realized it wasn't any good and I decided to fight to

get them to release me from being an aguna."

Arzi's battle

lasted 11 months. She documented the whole process in a detailed

journal. Her book describing, among other things, her protracted

struggle with the rabbinate will be published soon. "The place in

which a woman finds herself depends on her - on what she feels and

where she wants to be," she says.

On July 18, 1970, Rena

Hetz was caught in a similar predicament. The Phantom jet flown by

her husband, pilot Shmuel Hetz, and navigator Menachem Eini was hit

by anti-aircraft fire as it crossed the Suez Canal. The navigator

managed to eject from the plane. He was taken captive and returned

after three years. Hetz crashed with the plane on the ground.

"Hetz's death will forever remain a mystery," Eini wrote in his

book, "Halifat Lahatz" ("Pressure Suit"). "We'll never know what

happened in that fateful fraction of a second. Why didn't he get

out? Perhaps he was killed on the way out. Hetz took the secret of

his death and buried it, together with the smoking and shattered

Phantom, in the sands of Africa."

The search for Hetz's body

lasted for three years. For all of that time, his wife Rena was

considered an aguna. She did not seek to be released from that

status and the army did not propose it to her. Now, in retrospect,

she says that she was stuck in a kind of coma. "I trusted the air

force 100 percent," she says. "I also didn't check what they found

after three years. I don't know what was there in the coffin. From

talking to other pilots who took part in the battle with him, I

understood that he'd been killed. In the first three years, until

they found the body ... I anyway didn't have any thoughts of

marrying again, so the issue of being an aguna didn't bother me."

Rena Hetz never married again.

The turning point in the air

force's attitude toward agunot came in wake of the Yom Kippur War.

All the women who became agunot as a result of that war were freed

from this status after a year - whether they wished to be or not.

Tal Lev was one of those women. Her husband, Colonel Zurik Lev, was

the commander of the Ramat David Air Force Base and was due to be

appointed head of personnel. Even though he was not obligated to

fly, he decided to join the active pilots. On October 9, after being

hit by Egyptian fire, his Skyhawk plane fell into the sea near Port

Said. Pilots who were in the area did not see him parachuting.

Wide-ranging searches of the area came up completely empty. Lev left

behind his wife Tal and six children. Two years after his death, his

son Udi died of an asthma attack a few hours after Lev's memorial

service.

"Between all the emotional turmoil and the work of

raising the children, being an aguna didn't bother me," says Lev.

Several months after the plane crash - she doesn't remember the

exact date - a letter came in the mail informing her that she was

freed of her aguna status. "I felt like it was a matter of routine.

It was clear to me that he was gone. The letter didn't mean anything

to me. In any case, I didn't marry again. I was preoccupied with the

children and not with the issue of being an aguna."

Ora

Samuk, widow of pilot Gadi Samuk, had a different attitude. On

October 17, 1973, Samuk's plane was hit near the Suez Canal. Samuk

and the navigator, Baruch Golan, parachuted into Egyptian territory.

A few days later, their helmets were found near the crash site.

Searches of the area turned up nothing. A year after he disappeared,

Samuk was declared a casualty whose burial place is unknown, and Ora

Samuk was no longer an aguna.

But she was not totally

comfortable with the pronouncement of her husband's death. While

intelligence reports implied that the two had been killed by rural

Egyptians, she still hoped for his return and worried that no more

efforts to find him would be made once she was released from her

aginut. She resisted the official declaration of Gad Samuk as a

casualty with an unknown burial place, and refused to take his life

insurance. To this day, Samuk's body has never been found. In the

phone book, her name is listed alongside his. She has never

remarried.

Ruth Cohen was initially told that her husband,

Eran Cohen, was being held prisoner in Egypt. After a year, when it

was established that this was not the case, she was released from

aguna status. "The army hastened to release me, they said it was

good for me, but I wasn't able to digest the loss. They came to my

house to tell me that I was free. I refused to talk to them. They

came back a week later. The air force put serious pressure on me.

After two or three years, when I recovered a little, I understood

that this piece of paper had freed me, but I couldn't think about

that when I was still stunned with grief."

Cohen remarried.

"Since my second husband was a kohen (forbidden by Jewish law to

marry a divorcee) and I had also undergone halitza (a ceremony

releasing a widow from the halakhic obligation of marrying her

deceased husband's unmarried brother, thereby putting her on the

same legal footing as a divorcee) the rabbinate wouldn't agree to

marry us. After everything I'd been through, we had to get married

in a civil ceremony in Rome."

She had three children and

divorced after 14 years of marriage. "And that whole time I waited

for him. It was only in 1995, when they found his body, that I felt

relief. As long as there's no body and no grave, you can't live your

life serenely. It's a wound that doesn't heal. Every telephone call

made me jump. I was totally worn down. I'm sure that Tami Arad needs

a document freeing her from aguna status in order to be done with

this nightmare. Even though women like me walk a tightrope, since

this document is fateful. It's hard to accept the final

determination that he is dead when there's no grave, but it's just

as hard to live in uncertainty. And it's similarly hard to cope with

the husband's family. There's a problem because the parents object

to this pronouncement. There are two conflicting stances - that of

the parents and that of the widows."

The Eilat and the

Dakar

The question of the aginut of a woman married to a

military man was discussed back in the early days of the state, and

became the subject of a dispute between the chief rabbi at the time,

Yitzhak Herzog, and the chief IDF rabbi, Shlomo Goren. Herzog argued

that the chief rabbinate had prepared a form granting a conditional

get (religious divorce) for every combat soldier to sign. The

soldier's signature gave the rabbinical court permission to grant

his wife a get in the event of his disappearance. The conditional

formulation was intended to make possible the freeing of agunot

married to soldiers, because, in Jewish law, only the husband, and

not the court, is entitled to give the wife a divorce.

"Since no military order was given, in most cases, this was

not put into effect," Rabbi Herzog charged. Rabbi Goren countered

that he himself had prepared such a form, but that soldiers and

commanders had refused to sign it. "The commanders argued that

having soldiers sign a conditional get just before going into battle

would seriously hurt the troops' fighting morale and increase their

fear and concern for their families," he wrote in, "Meshiv Milhama"

(a book containing halakhic responsa on war-related questions).

"The soldiers themselves objected, saying that it would free

the government from having to worry about their wives." However,

even without the conditional permission form, Rabbi Goren did manage

to free agunot. On October 21, 1967, the destroyer Eilat sank after

coming under attack by Egyptian missiles. Of the 188 crewmen, 141

were rescued, 31 were killed and 16 were declared missing, including

seven married men. From talking with surviving members of the crew,

Rabbi Goren concluded that all of the missing had been killed.

"For each one of them, we have specific evidence of their

death or of their being seriously injured and with the conditions

and modes of rescue that prevailed at the time of the sinking,

anyone who wasn't pulled out and rushed to the hospital clearly died

in the water, either inside the ship or on deck," he wrote in

"Meshiv Milhama." In March 1969, all of the agunot whose husbands

had been on the Eilat were freed.

It was a similar story

with the women whose husbands were lost with the Dakar submarine,

which disappeared on January 25, 1968 on its maiden voyage from

England to Haifa. In June 1969, the agunot were freed on the basis

of several justifications. Jewish law stipulates that the wife of

someone who is lost in water "that has no end" will not be released

from aginut. A halakhic ruling from 450 years ago posited that the

judgment regarding someone who drowns within a room is the same as

that of a person who drowns in waters that do have an end. Rabbi

Goren ruled that the submarine was equivalent to a room and that,

therefore, the agunot could be released.

Goren also relied

on other reasoning, arguing that statistics prove that the rate of

survival from sunken submarines is virtually nil and thus the deaths

of 69 crewmen, including the married men among them, could be

assumed with certainty. He also said that there was no chance that

the crew had been taken captive since, "If all or part of the Dakar

crew was alive for such a long period of time, we, or other friendly

nations, would have gained knowledge of it."

"I felt that

[the release] was too hasty," says Nurit Manor, wife of Dakar sailor

Dan Manor. "I was a young mother with two baby girls. I was busy

with personal survival and with reorganizing my little family. The

aginut issue didn't bother me at all. One night - I remember that it

was 1:30 A.M. - I received a telegram informing me that I was no

longer an aguna. It was the funniest thing that had happened to me

since the submarine disappeared. I didn't understand what all the

rush was for. I feared that this step would put a halt to the search

for the submarine. It also seemed unfair to our husbands that they

should be so quickly declared dead."

However, the search was not discontinued; in 1999, the sunken submarine was finally located and an official state burial ceremony was held for its dead. Being freed of aguna status doesn't heal the aching soul, says Manor. "I don't know if Tami Arad will be able to feel free even after she is no longer considered an aguna. Formally, at least, it turns over a new page, but he missing person will always be with you. For many years, I dreamed about Dan at night. Even when I had another relationship and a new child, I was still married to the man who died on the submarine. A number of times, I dreamed that Dan returned and that I had to resolve the situation. Ten years after the Dakar was lost, I told Dan in a dream that he could stay with me even though I had a boyfriend and a child. 'I love you, too' I told him. It was only after they found the Dakar, two years ago, that I realized that it had to come to an end."